Types page

Learn how to declare types in TypeScript.

Overview

In this section, you will:

- Discover how to declare the various types used in TypeScript.

- Discuss how types can be inferred.

- Spot and correct basic type mistakes.

- Show how to assert types.

- Create a typed variable.

- Use type unions and intersections.

Objective 1: Primitives, objects, and arrays

Types explain what we can and cannot do with a value.

For instance, in JavaScript, you can access .length on strings but not on numbers.

Types also determine the outcomes when operators are applied to values.

Consider the + operator in the following JavaScript code:

console.info(a + b);

Some might interpret this as adding a and b, while others might see it as concatenating a and b.

Both interpretations could be correct, depending on the types of a and b.

If both are numbers, + performs addition; if both are strings, it performs concatenation.

This distinction hinges on their underlying types.

Note: If you are familiar with JavaScript’s primitive types you may recognize some of the names coming up. The types

stringbooleanandnumbershould feel familiar. These types are the same in TypeScript as they are in JavaScript and are often referred to as primitive types.

Boolean

The boolean type is one of the simplest types in TypeScript. It can only be true or false.

const isCarnivore: boolean = true;

const isHerbivore: boolean = false;

Number

All numeric values in TypeScript are represented by the number type.

If you are familiar with other typed languages (e.g. C++), you may be familiar with specific number types like integers and floats.

In TypeScript, there is only number.

const teeth: number = 100;

const hex: number = 0xf00d;

String

The string type is used to represent textual data.

It’s similar to strings in JavaScript and can be enclosed in single quotes, double quotes, or backticks.

const name: string = "Leoplurodon";

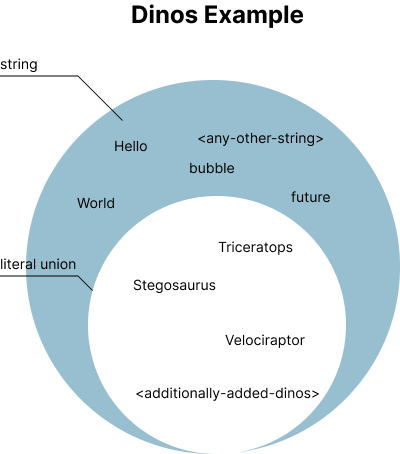

Literals

In TypeScript, there is a subset within string, number, and boolean which allows us to refine the specificity of the type.

These are called type literals. A string literal is a single string for example:

type StringLiteralExample = "hello";

If we were to assign a variable with this StringLiteralExample type we declared, we would see the only value it can be is "hello".

const invalid: StringLiteralExample = "a";

const valid: StringLiteralExample = "hello";

In this case, invalid will return an error.

What we have done is restricted the string type to be only the single string "hello".

The same can be done with number values, and less helpfully, boolean values.

Literals like this are very powerful when used together with type unions. They allow us to expand our subset to include multiple values.

type Dino = "Stegosaurus" | "Triceratops" | "Velociraptor";

Note: In TypeScript projects and applications, unions are often used as a low-overhead version of enums.

While we spent the time going over what a literal is, for the remainder of this section (and sections to come), we will not make the distinction between type literals and types because literals are types.

Array

Arrays hold multiple values of the same type. Arrays can be written in one of two ways:

const numberList: number[] = [1, 2, 3];

const raptorNames: Array<string> = ["Blue", "Charlie", "Delta"];

The numberList array will only contain number values, while raptorNames will only contain string values.

If we wanted to be even more specific:

type Dino = "Stegosaurus" | "Triceratops" | "Velociraptor";

const raptors: Array<Dino> = ["Steogosaurus", "Triceratops", "Delta"];

The raptors variable now only accepts what’s provided by the string literal Dino.

But wait! There’s something wrong with the array we’ve provided in raptors. One of these things is not like the other. Since Delta isn’t a part of the string literal provided, we’ll get the error:

Type '"Delta"' is not assignable to type 'Dino'.

Which one should you use?

The bracket notation (Dino[]) is much cleaner and easier to read, but is also easy to miss in a large definition, as in this example:

type Dinos = {

type: "land";

name: string;

distanceAbleToWalk: number;

legLength: number;

}[];

Because of this, we recommend using bracket notation for simple types and using the full array notation for complex types.

Object

Another basic JavaScript type, Object, can be used to more descriptively type a variable.

const user: { name: string; age: number } = { name: "Justin", age: 36 };

Later we will learn about Interfaces, which are a better way of describing Object values because the type can be reused.

Setup 1

✏️ Create src/types/fix-errors.ts and update it to be:

let isLoading: boolean;

isLoading = true;

isLoading = "false";

let inventory: Array<number> = [];

inventory.push("tacos", "hamburgers");

function greet(name: string, age: number): string {

return `${name} is ${age} years young.`;

}

export const jessica = greet(30, "Jessica");

export const tom = greet("Tom", 42, "software");

export { isLoading, inventory };

Verify 1

✏️ Create src/types/fix-errors.test.ts and update it to be:

import assert from "node:assert/strict";

import { describe, it } from "node:test";

import { jessica, tom, isLoading, inventory } from "./fix-errors";

describe("Fix Errors", () => {

it("types are correct", function () {

assert.equal(isLoading, false, "isLoading");

assert.deepEqual(inventory, ["tacos", "hamburgers"], "inventory");

assert.equal(jessica, `Jessica is 30 years young.`, "jessica");

assert.equal(tom, `Tom is 42 years young.`, "Tom");

});

});

Exercise 1

The src/types/fix-errors.ts file currently has the following errors:

TSError: ⨯ Unable to compile TypeScript:

src/types/fix-errors.ts(3,1): error TS2322: Type 'string' is not assignable to type 'boolean'.

src/types/fix-errors.ts(7,16): error TS2345: Argument of type 'string' is not assignable to parameter of type 'number'.

src/types/fix-errors.ts(13,30): error TS2345: Argument of type 'number' is not assignable to parameter of type 'string'.

src/types/fix-errors.ts(15,37): error TS2554: Expected 2 arguments, but got 3.

Do the following:

- Fix the assigned value to

isLoading. - Fix the type in the Array for

inventory. - Fix the order of the arguments for

jessica. - Fix the function call for

tom.

Having issues with your local setup? You can use either StackBlitz or CodeSandbox to do this exercise in an online code editor.

Solution 1

If you’ve implemented the solution correctly, the tests will pass when you run npm run test!

Click to see the solution

✏️ Update src/types/fix-errors.ts to look like:

let isLoading: boolean;

isLoading = true;

isLoading = false;

let inventory: Array<string> = [];

inventory.push("tacos", "hamburgers");

function greet(name: string, age: number): string {

return `${name} is ${age} years young.`;

}

export const jessica = greet("Jessica", 30);

export const tom = greet("Tom", 42);

export { isLoading, inventory };

Having issues with your local setup? See the solution in StackBlitz or CodeSandbox.

Objective 2: More types and typed variables

Tuple

A “tuple” is a typed array with a pre-defined length. Each index is capable of having its own type.

type Dino = "Stegosaurus" | "Triceratops" | "Velociraptor";

let dinoTuple: [number, string, Dino];

dinoTuple = [5, "boop", "Stegosaurus"];

dinoTuple = ["boop", "Stegosaurus", 5];

First we give dinoTuple the assignment [5, "boop", "Stegosaurus"], based on the tuple we’ve provided [number, string, Dino] it looks like we’re following the typing rules, so there’ll be no errors.

Then, we mutate dinoTuple to be ["boop", "Stegosaurus", 5] everything’s out of order, but we only get two type errors here.

For boop: Type 'string' is not assignable to type 'number'.

and for 5: Type 'number' is not assignable to type 'Dino'.

Both of these make sense, and while we intended Stegosaurus to line up with its StringLiteral typing provided by Dino, it still is a string.

Enum

Enums allow the aliasing of names to a list of numeric values. Like most indexing, enums start their first member at 0.

enum Color {

Red,

Green,

Blue,

}

const greenColor: Color = Color.Green;

Enums can have their first value manually set:

enum Month {

January = 1,

February,

March,

April,

May,

June,

}

const feb = Month[2];

Or manually set all values:

enum Month {

January = 1,

March = 3,

May = 5,

}

const may = Month[5];

String unions as enums

An alternative to full enums is to use a union of strings. This has a few benefits:

- It doesn't require an import to use.

- It preserves the human-readable values for debugging.

Example:

// instead of

enum Color {

Red,

Green,

Blue,

}

// try

type Color = "Red" | "Green" | "Blue";

Unknown

Unknown describes a variable where we may not know the type. Variables defined with the unknown type can later be narrowed to more specific types using typeof checks or comparisons.

Note that variables of type unknown have no accessible properties or functions.

let value: unknown = 5;

value = "words";

value.length; // Will give "Object is of type unknown" error

// Will give "Type unknown is not assignable to type string" error

const value2: string = value;

// Check type using typeof

if (typeof value === "string") {

// Can successfully narrow

const stringValue: string = value;

console.info("Length is", stringValue.length);

}

Any

The any type is useful when we want to opt-out of type checking.

Using the any type will disable all compile-time checks, including access to properties and functions.

This is mostly useful for third-party data structures that we do not know the shape of, or when incrementally opting in to types.

Otherwise, it is not advised to use theany type, so do your best to provide typing for data that you’re using.

let my3rdPartyData: any = 5;

my3rdPartyData = "five";

my3rdPartyData.invalidFunction(3);

Void

No type at all — commonly used with functions that don’t return a value.

function buttonClick(): void {

console.info("I clicked a button that returns nothing");

}

Never

The never type represents a value that will never occur.

function error(message: string): never {

throw new Error(message);

}

When an error is thrown in the scope of a function that function doesn’t return, so this is an instance where never is an appropriate return type.

Type inference

When we don’t provide explicit types for our variables, TypeScript will do its best to infer the types, and it’s very good at it. The following code will not compile due to type inference.

let name = "Sally";

const height = 6;

name = height;

// Type 'number' is not assignable to type 'string'

Type can also be inferred from complex objects.

const person = {

name: "Sally",

height: 6,

address: {

number: 555,

street: "Rodeo Drive",

},

};

person.name = "Cecilia";

// Works

person.name = 6;

// Type '6' is not assignable to type 'string'.

person.address.number = "five fifty-five";

// Type '"five fifty-five"' is not assignable to type 'number'.

Dangers of type inference

Be forewarned that type inference can come with some dangers. Among others, any string-like value will be inferred as a string. This can have unintended consequences when you intend those types to be more specific. For example:

type Dino = "Stegosaurus" | "Triceratops" | "Velociraptor";

const dinosaur = {

name: "Sally",

kind: "Stegosaurus",

};

// this is allowed, but shouldn't be

dinosaur.kind = "Unicorn";

One solution is to use an assertion:

type Dino = "Stegosaurus" | "Triceratops" | "Velociraptor";

const dinosaur = {

name: "Sally",

kind: "Stegosaurus" as Dino,

};

// this is not allowed

dinosaur.kind = "Unicorn";

Another would be to avoid inference altogether.

Type inference for functions

TypeScript will infer the return value of functions as well.

function multiplier(a: number, b: number) {

return a * b;

}

var multiplied: number = multiplier(2, 3);

// Works

var str: string;

str = multiplier(10, 20);

// Type 'number' is not assignable to type 'string'.

Type inference can be a very helpful tool in refactoring code and helping better document expectations for our code. However, many code bases require explicit return types on all functions or on exported functions.

- It acts as another test, validating that your function returns what you expect.

- It ensures your function API is stable.

- It makes type errors easier to debug.

Type assertions

Type assertions are a way to override the inferring of types, with the as keyword:

const otherValue: any = "this is a string";

const otherLength: number = (otherValue as string).length;

Type assertions should be used sparingly, however.

Objective 3: Intersections and Unions

Intersections

There are many different ways to create new types from existing ones in TypeScript. Intersections allow us to create a type containing all the properties of multiple types together. Put another way: Intersections combine multiple types into one.

Let’s imagine we have the following types:

type Person = {

age: number;

name: string;

};

type AnimalTrainer = {

animals: Array<Animals>;

level: "rookie" | "intermediate" | "advanced";

};

However, we also need a DinosaurCareTaker. A dinosaur caretaker is a Person and an AnimalTrainer.

Intersections allow us to create a type from Person and DinosaurCareTaker using the & symbol.

type DinosaurCareTaker = Person & AnimalTrainer;

/**

* {

* name: string;

* age: number;

* level: "rookie" | "intermediate" | "advanced";

* animals: Array<Animals>;

* }

*/

DinosaurCareTaker looks good, but there is more to being a dinosaur caretaker than being a Person and an AnimalTrainer. Luckily, there can be more than one intersection in a type declaration, and we can add the specifics of DinosaurCareTaker in another intersection.

type DinosaurCareTaker = Person &

AnimalTrainer & {

dinosaurName: string;

dinosaurType: "carnivore" | "herbivore";

};

/**

* {

* name: string;

* age: number;

* level: "rookie" | "intermediate" | "advanced";

* animals: Array<Animals>;

* dinosaurName: string;

* dinosaurType: "carnivore" | "herbivore";

* }

*/

There are a couple of things to be aware of when using type intersections. One is that order doesn’t matter since the intersection operator (&) is associative. This means the following two types (A and B) are the same.

type A = Foo & Bar;

type B = Bar & Foo;

One catch with intersections is giving them types that can’t be reconciled together. For example, creating a type from the intersection of two string unions:

type Union1 = "hello" | "world";

type Union2 = "person" | "animal";

type Intersection = Union1 & Union2;

…or trying to create a type from the intersection of two types that share a key name but the type of the key is different in both types:

type Object1 = {

name: string;

age: number;

};

type Object2 = {

description: string;

age: string;

};

type Intersection = Object1 & Object2;

In this case, the shared key is age, while the differing types are number and string.

Both of these will appear to work, however, when used, the Intersection type will be never at the age key and you’ll get an error along the lines of:

Type 'Intersection' is not assignable to type 'never'.ts(2322)

We will learn more about never below!

Type unions

In the earlier sections, we saw how we could make unions from primitive type literals; however, unions extend beyond the primitives. This section will explore how type unions work with object types.

Type unions allow us to create a single type from two or more different types. Imagine we have the following:

type LandDinosaur = {

name: string;

distanceAbleToWalk: number;

legLength: number;

};

type AirDinosaur = {

name: string;

distanceAbleToFly: number;

wingLength: number;

};

type WaterDinosaur = {

name: string;

distanceAbleToSwim: number;

finLength: number;

};

Functions will be covered in the next section!

And we have to implement a getTotalDistanceAbleToTravel function that takes any number of dinosaurs and computes how far they could move. Given the current tools in our arsenal, we could create something along the lines of this:

function getTotalDistanceAbleToTravelOnLand(quadDino: LandDinosaur[]): number {

return quadDino.reduce((total, dino) => total + dino.distanceAbleToWalk, 0);

}

function getTotalDistanceAbleToTravelInAir(wingDino: AirDinosaur[]): number {

return wingDino.reduce((total, dino) => total + dino.distanceAbleToFly, 0);

}

function getTotalDistanceAbleToTravelInWater(

waterDino: WaterDinosaur[]

): number {

return waterDino.reduce((total, dino) => total + dino.distanceAbleToSwim, 0);

}

This works, but it’d be a pain to have to figure out which dinosaur we have and then select the correct function to use for that dinosaur group. It’d be nice if we could pass our dinosaurs to a single function and get the result we’re after.

Currently, our typing is the limitation stopping us from achieving this. This is where type unions can make a big impact in our code. Type unions use the | (pipe) operator to combine any number of different types and can be read as or. This allows us to create a Dinosaur type that is either a LandDinosaur, an AirDinosaur, or a WaterDinosaur.

type Dinosaur = AirDinosaur | WaterDinosaur | LandDinosaur;

function getTotalDistanceAbleToTravel(dinos: Dinosaur[]): number {

// ...

}

This solves our function signature problem and allows us to pass any collection of dinosaurs to our function. However, this introduces two new problems.

Object creation

The first problem comes when creating a dinosaur object. Union types simplify creating an object — we need to pass it keys from any of the types in the union. The only keys that are required are the ones that are shared across all types in the union.

In our case, the only shared key across LandDinosaur, AirDinosaur, and WaterDinosaur is name; anything else is fair game to add as long as the keys are from the same type.

This means we can get type-safe objects that don’t make a lot of sense. Take, for example, this pterodactyl object.

const pterodactyl: Dinosaur = {

name: "pterodactyl",

distanceAbleToSwim: 500,

distanceAbleToFly: 900,

finLength: 60,

wingLength: 10,

};

According to TypeScript, type-wise, it is correct, but it doesn’t really make a lot of sense since pterodactyls don’t have fins, and in the context of our types and the function we’re trying to write should only have a distanceAbleToFly property rather than an additional distanceAbleToSwim.

A common solution is to update our types a little to give TypeScript a hint as to what keys can go with each other. We do this by providing a common key across all types and assigning them to a type literal.

In our case, a string literal would provide the most semantic sense, so we will use that. Let’s add a type key to our three types and try to create the pterodactyl object again.

type LandDinosaur = {

type: "land";

name: string;

distanceAbleToWalk: number;

legLength: number;

};

type AirDinosaur = {

type: "air";

name: string;

distanceAbleToFly: number;

wingLength: number;

};

type WaterDinosaur = {

type: "water";

name: string;

distanceAbleToSwim: number;

finLength: number;

};

const pterodactyl: Dinosaur = {

type: "air",

name: "pterodactyl",

distanceAbleToSwim: 500, // ERROR see below

distanceAbleToFly: 900,

finLength: 60,

};

We get an error that says:

Type '{ type: "air"; name: string; distanceAbleToSwim: number; distanceAbleToFly: number; finLength: number; }' is not assignable to type 'Dinosaur'.

Object literal may only specify known properties, but 'distanceAbleToSwim' does not exist in type 'AirDinosaur'. Did you mean to write 'distanceAbleToFly'?

This translates to, “you said it’d be an AirDinosaur, but you gave me some stuff not on AirDinosaur". This solves our first problem of creating objects.

Object use

The second problem with our solution comes with using our typed parameter in our function. Which looks like this:

type Dinosaur = AirDinosaur | WaterDinosaur | LandDinosaur;

function getTotalDistanceAbleToTravel(dinos: Dinosaur[]): number {

return dinos.reduce((total, nextDino) => {

/** ... */

}, 0);

}

If we try to use nextDino, there will only be two properties available to us — name and type.

This is because TypeScript has no idea which type of dinosaur has been passed to it, so the only thing it can say exists on the object is the ones that are shared across all types comprising the union. In order for us to be able to use the distance and length properties of the different dinosaurs, we need to go through a process called type narrowing.

Type narrowing allows us to move from a more general type (like Dinosaur) to a more specific type (like AirDinosaur). There are many ways for us to do this, one being a type literal unique to each type which, luckily for us, we have already implemented when solving the first issue.

To type narrow, we first check the type with an if or switch statement. Inside the context of that conditional TypeScript is able to discern which type the nextDino is!

function getTotalDistanceAbleToTravel(dinos: Dinosaur[]): number {

return dinos.reduce((total, nextDino) => {

if (nextDino.type === "air") {

return total + nextDino.distanceAbleToFly;

}

if (nextDino.type === "water") {

return total + nextDino.distanceAbleToSwim;

}

if (nextDino.type === "land") {

return total + nextDino.distanceAbleToWalk;

}

return total;

}, 0);

}

Note: TypeScript is smart enough to figure out that there are only three types. If we had checked for the first two (air and water), it would know that the third must be land even if we didn't have that in a condition. Including the third condition and

return totalhelps future-proof our code, however.

Setup 3

✏️ Create src/types/character.ts and update it to be:

interface BaseCharacter {

strength: number;

dexterity: number;

intelligence: number;

}

interface Warrior {

weapon: "Sword";

}

interface Wizard {

weapon: "Staff";

magic: true;

}

interface Rogue {

weapon: "Bow";

}

type Character = never;

export const fighter: Character = {

strength: 15,

dexterity: 10,

intelligence: 8,

weapon: "Sword",

};

export const mage: Character = {

strength: 5,

dexterity: 8,

intelligence: 15,

weapon: "Staff",

magic: true,

};

export const thief: Character = {

strength: 10,

dexterity: 15,

intelligence: 8,

weapon: "Bow",

};

export const paladin: Character = {

strength: 15,

dexterity: 10,

intelligence: 8,

weapon: "Sword",

// @ts-expect-error: a sword character cannot be magic!

magic: true,

};

// @ts-expect-error: a weapon is required on the Character type!

export const civilian: Character = {

strength: 8,

dexterity: 8,

intelligence: 8,

};

✏️ Create src/types/food.ts and update it to be:

interface Sushi {

cuisine: "Japanese";

fish: string;

}

interface Taco {

cuisine: "Mexican";

meat: string;

}

interface Curry {

cuisine: "Indian";

spicy: number;

}

type Dish = never;

export const sushi: Dish = {

cuisine: "Japanese",

fish: "Tuna",

};

export const taco: Dish = {

cuisine: "Mexican",

meat: "Chicken",

};

export const curry: Dish = {

cuisine: "Indian",

spicy: 10,

};

export const fusion: Dish = {

cuisine: "Japanese",

// @ts-expect-error: spicy doesn’t exist on the Sushi interface!

spicy: 5,

};

Verify 3

✏️ Create src/types/character.test.ts and update it to be:

import assert from "node:assert/strict";

import { describe, it } from "node:test";

import { fighter, mage, thief, paladin, civilian } from "./character";

describe("Character tests", () => {

it("works as expected", function () {

assert.ok(fighter.weapon === "Sword", "works");

assert.ok(mage.weapon === "Staff", "works");

assert.ok(thief.weapon === "Bow", "works");

assert.ok(paladin.weapon === "Sword", "works");

assert.ok(civilian.strength === 8, "works");

});

});

✏️ Create src/types/food.test.ts and update it to be:

import assert from "node:assert/strict";

import { describe, it } from "node:test";

import { sushi, taco, curry, fusion } from "./food";

describe("Food tests", () => {

it("works as expected", function () {

assert.ok(sushi.cuisine === "Japanese", "works");

assert.ok(taco.cuisine === "Mexican", "works");

assert.ok(curry.cuisine === "Indian", "works");

assert.ok(fusion.cuisine === "Japanese", "works");

});

});

Exercise 3

In this exercise, we will fix the TypeScript errors by using a combination of type unions and intersections.

In character.ts, update the

Charactertype so that the TypeScript errors are resolved forfighter,mage, andthief. Thepaladinandciviliantype are expected to give errors.In food.ts, update the

Dishtype so that the TypeScript errors are resolved forsushi,taco, andcurry. Thefusiontype is expected to give an error.

Having issues with your local setup? You can use either StackBlitz or CodeSandbox to do this exercise in an online code editor.

Solution 3

If you’ve implemented the solution correctly, the tests will pass when you run npm run test!

Click to see the solution

✏️ Update character.ts so that Character is an intersection of BaseCharacter and a union of Warrior, Wizard, and Rogue.

interface BaseCharacter {

strength: number;

dexterity: number;

intelligence: number;

}

interface Warrior {

weapon: "Sword";

}

interface Wizard {

weapon: "Staff";

magic: true;

}

interface Rogue {

weapon: "Bow";

}

type Character = BaseCharacter & (Warrior | Wizard | Rogue);

export const fighter: Character = {

strength: 15,

dexterity: 10,

intelligence: 8,

weapon: "Sword",

};

export const mage: Character = {

strength: 5,

dexterity: 8,

intelligence: 15,

weapon: "Staff",

magic: true,

};

export const thief: Character = {

strength: 10,

dexterity: 15,

intelligence: 8,

weapon: "Bow",

};

export const paladin: Character = {

strength: 15,

dexterity: 10,

intelligence: 8,

weapon: "Sword",

// @ts-expect-error: a sword character cannot be magic!

magic: true,

};

// @ts-expect-error: a weapon is required on the Character type!

export const civilian: Character = {

strength: 8,

dexterity: 8,

intelligence: 8,

};

✏️ Update food.ts so that Dish is a union of Sushi, Taco, and Curry.

interface Sushi {

cuisine: "Japanese";

fish: string;

}

interface Taco {

cuisine: "Mexican";

meat: string;

}

interface Curry {

cuisine: "Indian";

spicy: number;

}

type Dish = Sushi | Taco | Curry;

export const sushi: Dish = {

cuisine: "Japanese",

fish: "Tuna",

};

export const taco: Dish = {

cuisine: "Mexican",

meat: "Chicken",

};

export const curry: Dish = {

cuisine: "Indian",

spicy: 10,

};

export const fusion: Dish = {

cuisine: "Japanese",

// @ts-expect-error: spicy doesn’t exist on the Sushi interface!

spicy: 5,

};

Having issues with your local setup? See the solution in StackBlitz or CodeSandbox.

Next steps

Next up, we’ll be using TypeScript to annotate functions.